Timothy Snyder, in his book Black Earth: The Holocaust as History and Warning, writes “if Jews were to be removed from the planet, they first had to be separated from the state.” He also quotes Hannah Arendt: “One can only do what one likes with stateless people. […] The first, fundamental step on the way to total domination is to kill the legal entity of a person.”

The abolition of the Jewish nationality and the deprivation of their citizenship were an integral part of the Third Reich’s extermination plans. Jews who had German, French, Danish or Bulgarian citizenship before the outbreak of the war had a much better chance of survival than Polish Jews; these had the “worthless” citizenship of a country destroyed by Germany in 1939. One example is the situation of French Jews, around 75% of whom survived the Holocaust, while at the same time nearly 30,000 Polish Jews living in France during the war were murdered as stateless entities. Therefore, often the only way to save Jews was to have access to legal and official mechanisms that could prevent them from being deported to extermination camps.

In this situation, only diplomats with the appropriate documents and tools were able to help the Jewish population on a larger scale. They could grant citizenship to existing states, for example Sweden or Paraguay, in order to restore legal status to Jews residing in territories controlled by the Third Reich and save them from death. Even entering a name on a list of Palestinian citizens, a mandate territory of Great Britain, was enough to save the lives of entire families in Poland. This was the case of Henryk Schönker and his relatives, who left the ghetto in Tarnów with a miraculously-obtained confirmation of Palestinian citizenship, and survived to witness the end of the war in Bergen-Belsen (as described by Schönker in The Touch of an Angel). Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg saved thousands of lives by issuing nearly 15,000 “protective passports”. The Spanish consul Eduardo Propper de Callejón and the Portuguese consul Aristides de Sousa Mendes issued thousands of transit documents to the Jews fleeing France, which allowed them to continue their journey, mainly to the United States. Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese consul in Kaunas made it possible for nearly 8,000 Jews to leave Europe with the aid of Polish intelligence officers.

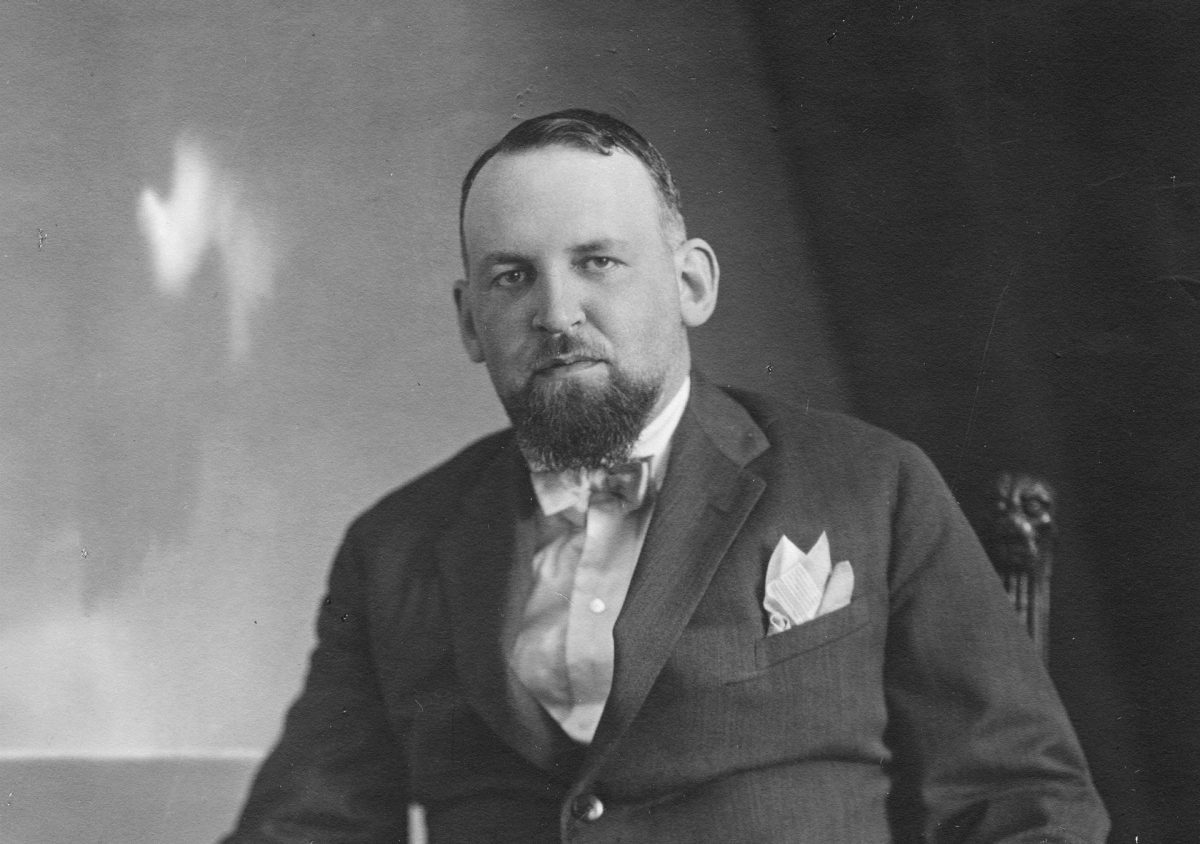

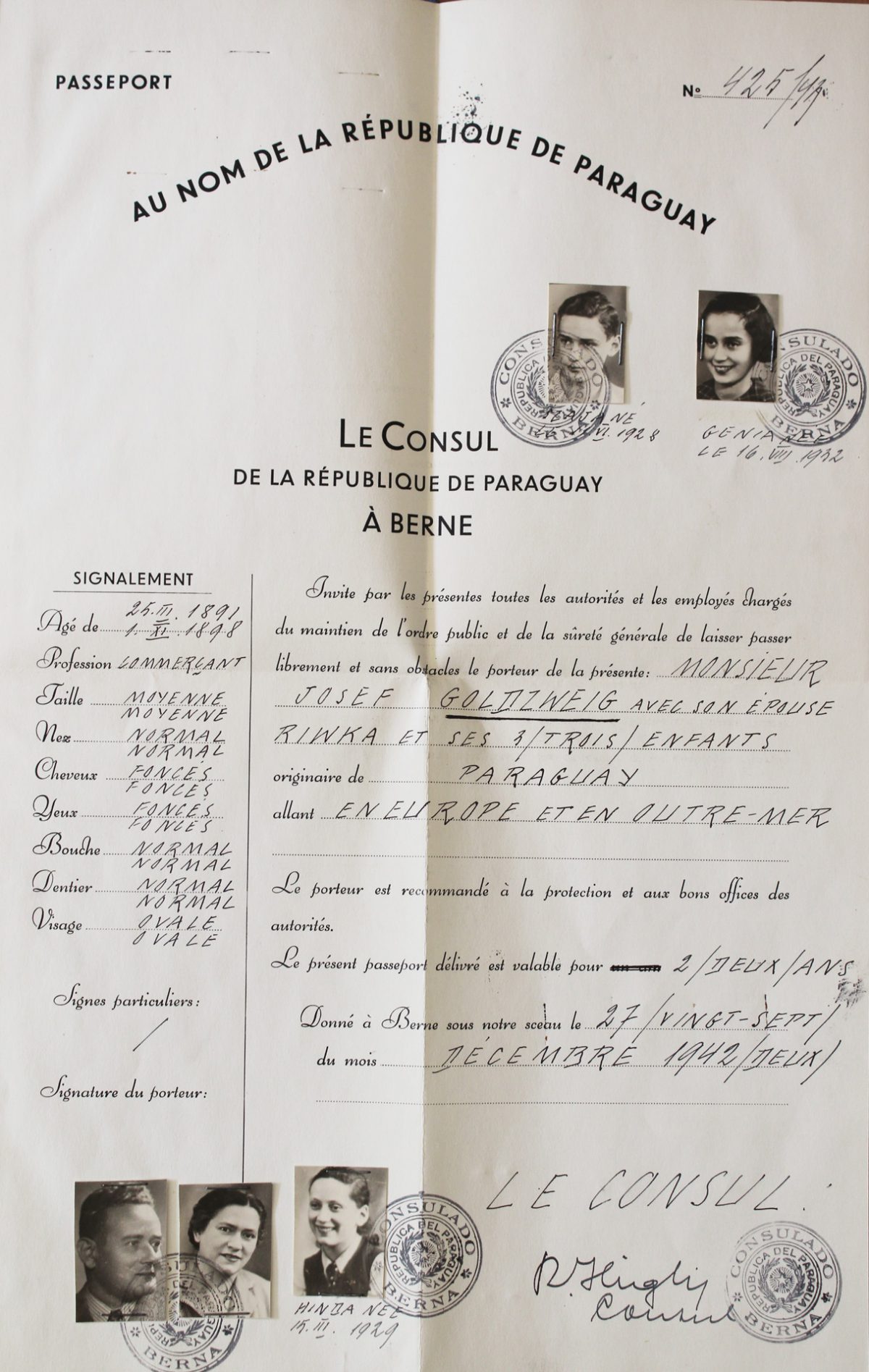

The passport campaign conducted by the Polish diplomatic mission in Bern, in cooperation with Jewish organizations, had the financial and political backing of the Polish government-in-exile. The forgery of thousands of documents from Latin American countries (Paraguay, Honduras, Haiti and Peru) by Polish diplomats became a means to grant citizenship to Jews living in ghettos not only in Poland, but throughout occupied Europe. For several years now the Pilecki Institute, in cooperation with Polish and foreign partners, has been conducting archival research and scientific studies into the activities of the Ładoś Group. Passports for life gathers and presents the current knowledge about the actions of the Polish diplomats in Bern.

Hanna Radziejowska (Pilecki Institut)