Uncle „Passport”

Arie Liwer

Five young Jews in Poland, apparently visiting a family of farmers in the country. The photo was taken in the 1930s. Arie Liwer (front).

Courtesy of the Ghetto Fighters’ House Archives, Israel

Young Jews in 1930s Poland, probably members of the Gordonia movement. Arie Liwer (center).

Courtesy of the Ghetto Fighters’ House Archives, Israel

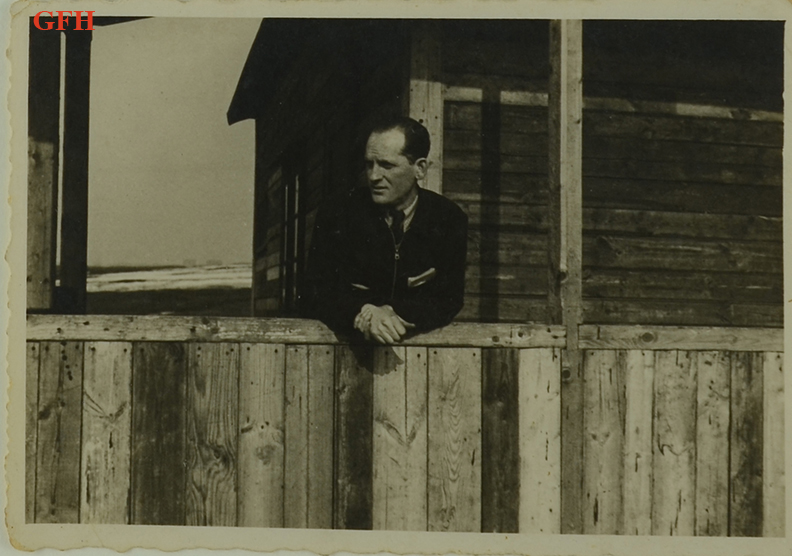

Arie Liwer, a member of the Gordonia and Hitahdut movements in Poland. The photo was taken at the "Farma", an agricultural farm run by Zionist youth movements in Srodula, near Sosnowiec.

Courtesy of the Ghetto Fighters’ House Archives, Israel

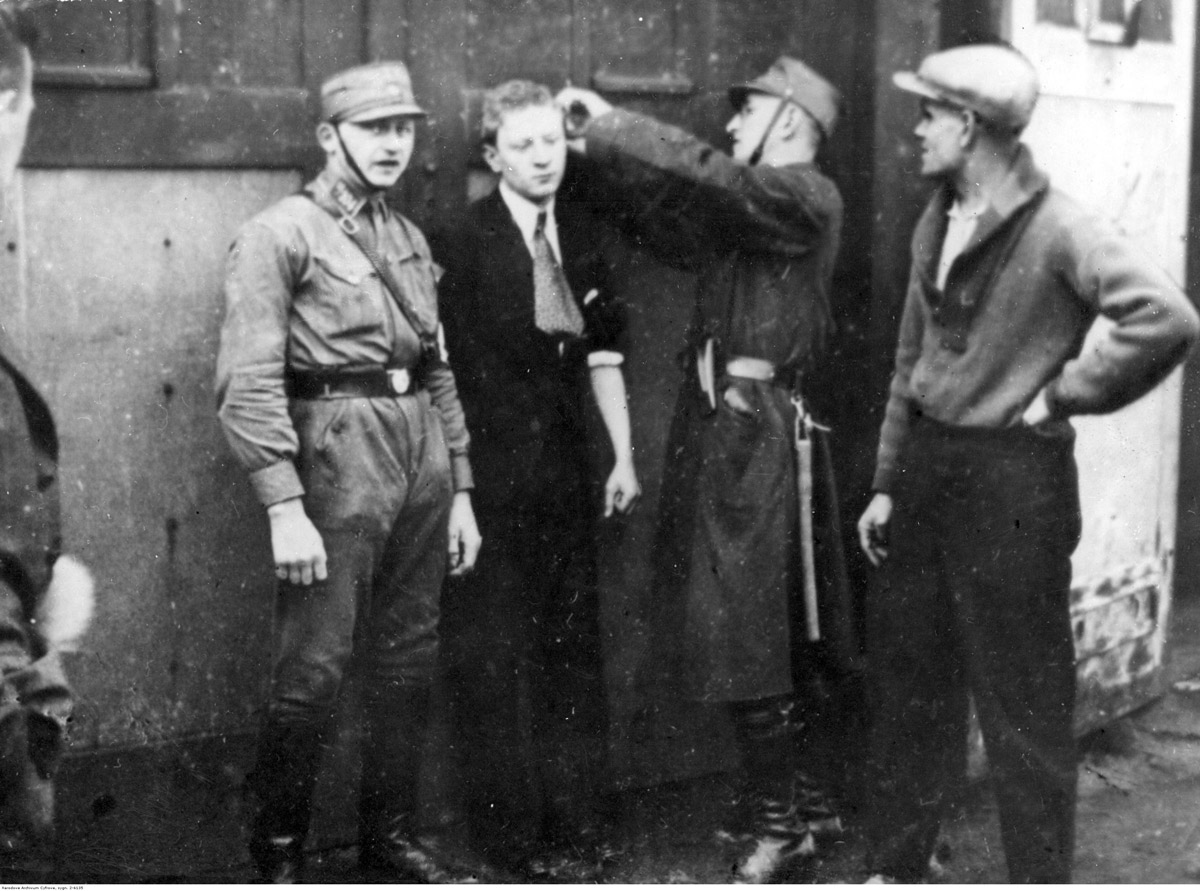

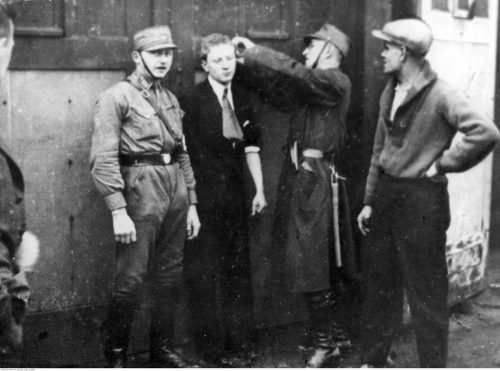

An SA man cuts a young Jew’s hair.

National Digital Archives

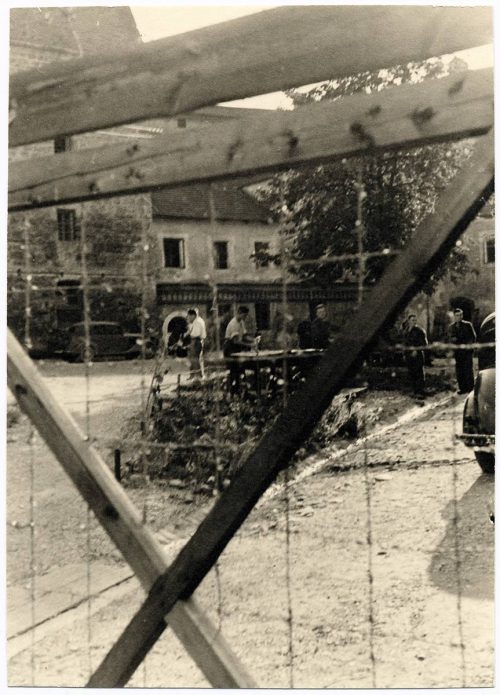

Będzin, 1933. The tower of St. Trinity Church is visible in the background.

National Digital Archives

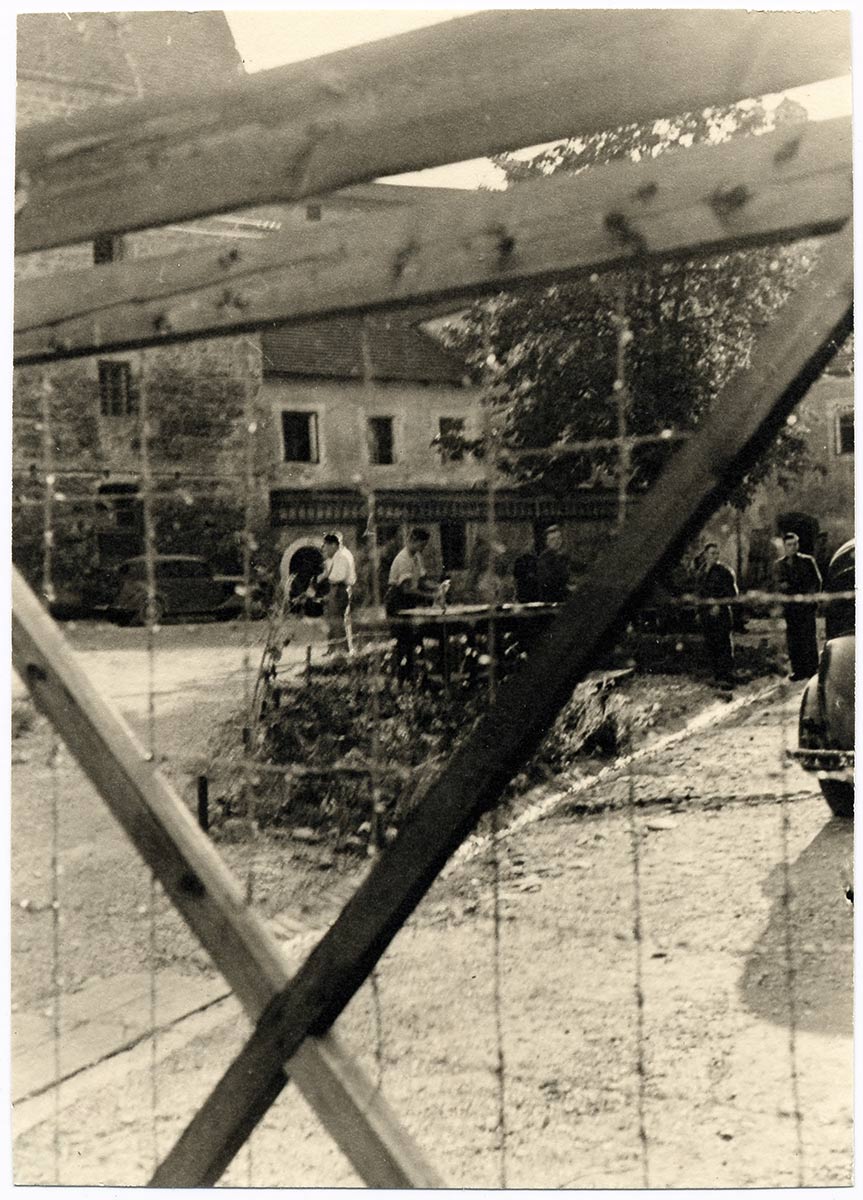

Tittmoning. Ilag, Prisoners of war camp. View inside the camp

copyright International Committee of the Red Cross ICRC, 12/10/1942, War 1939-1945., V-P-HIST-02295-10

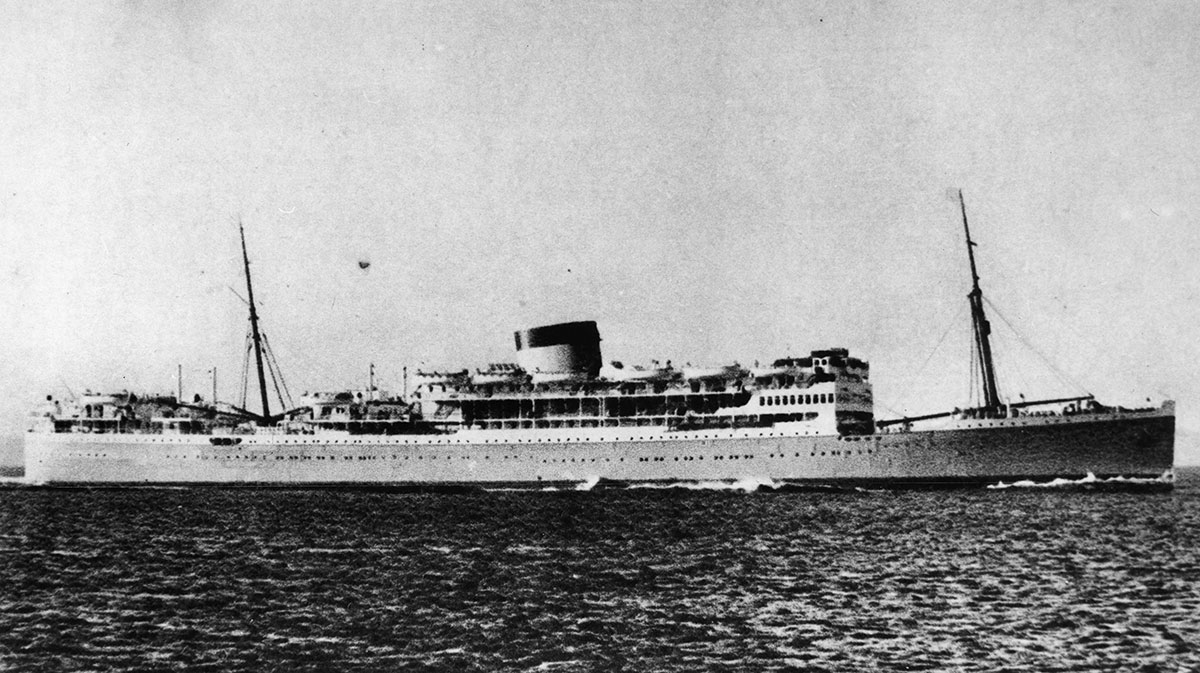

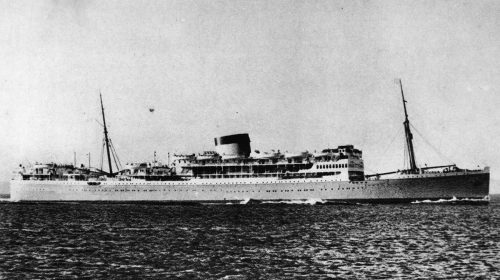

Winchester Castle (ship)

State Library of Queensland