History of the Lichtenstern family

Heidi Fishman's family – Margaret Lichtenstern with her son Robbie and daughter Ruth

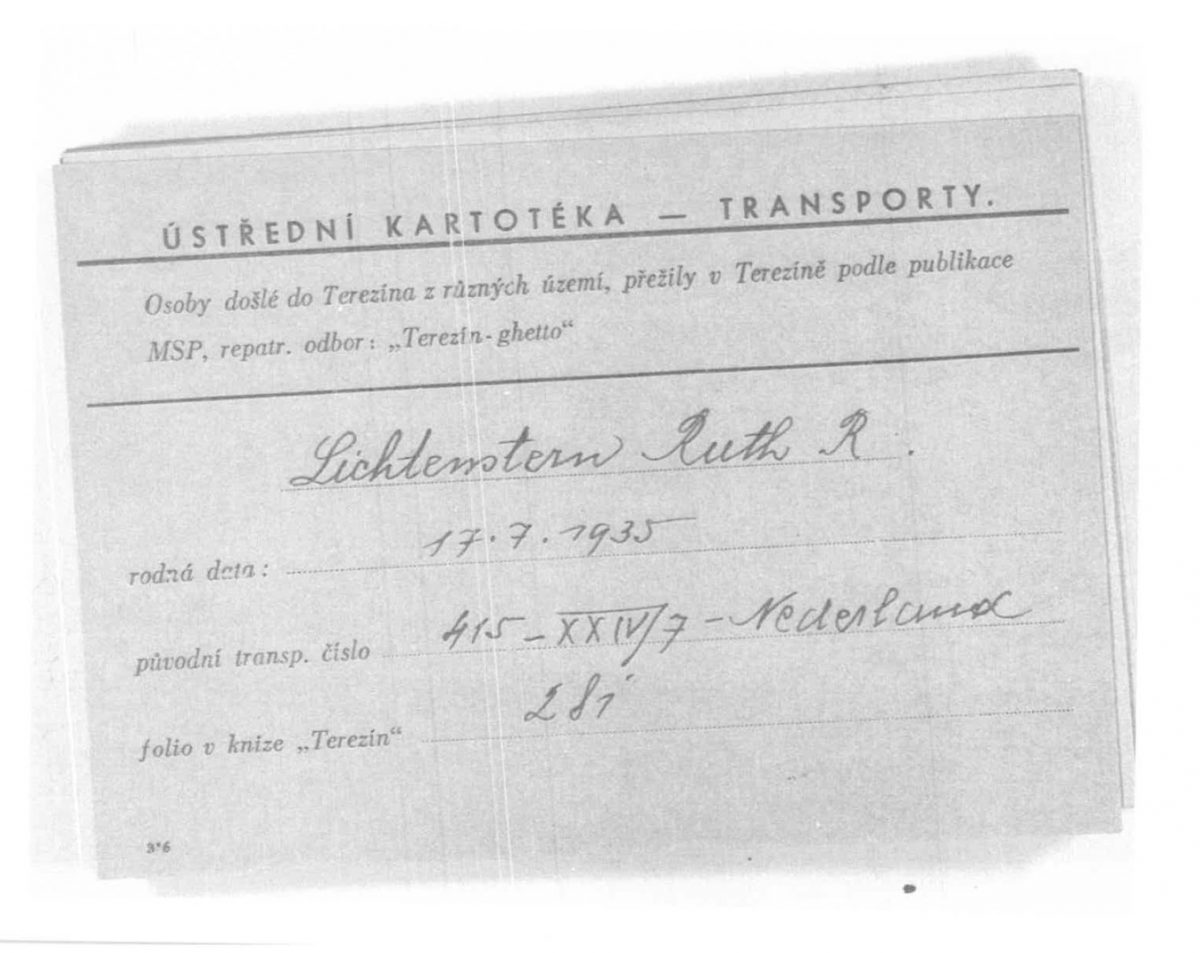

Heidi's mother – Ruth „Tutti” Lichtenstern

Fishman, 1944

Heidi's uncle – Robbie

Lichtenstern, 1944

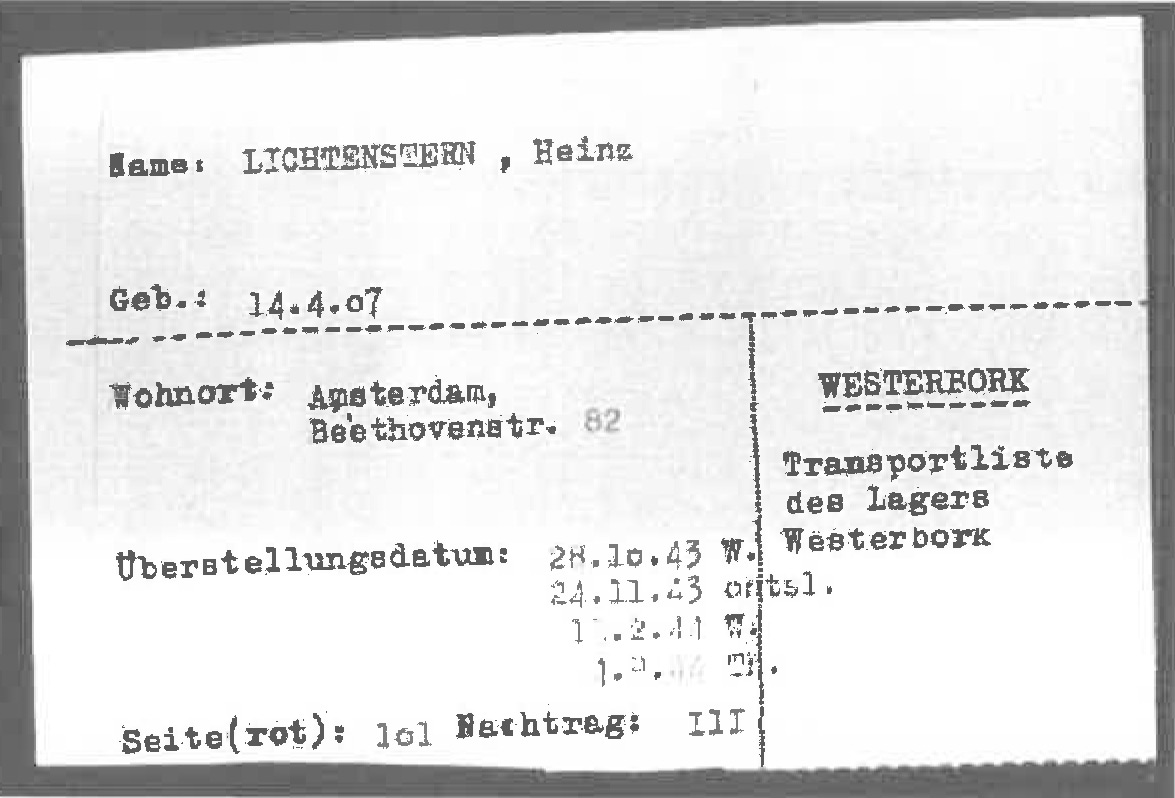

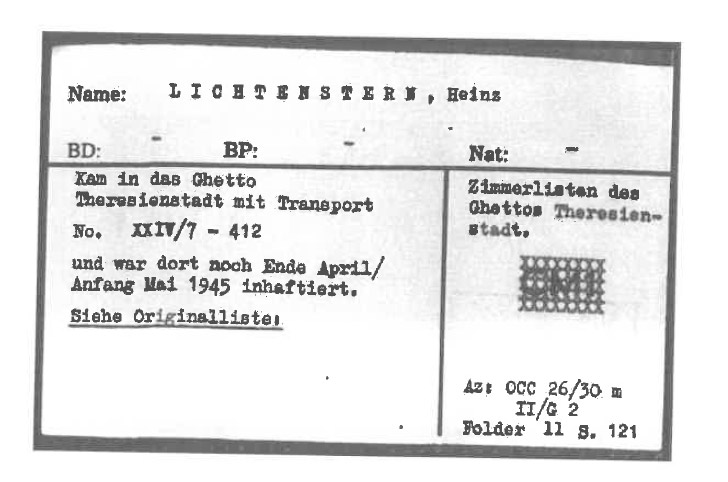

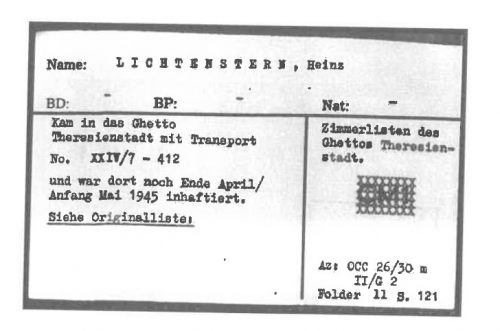

Document No 65523624#1

ITS Arolsen Archives

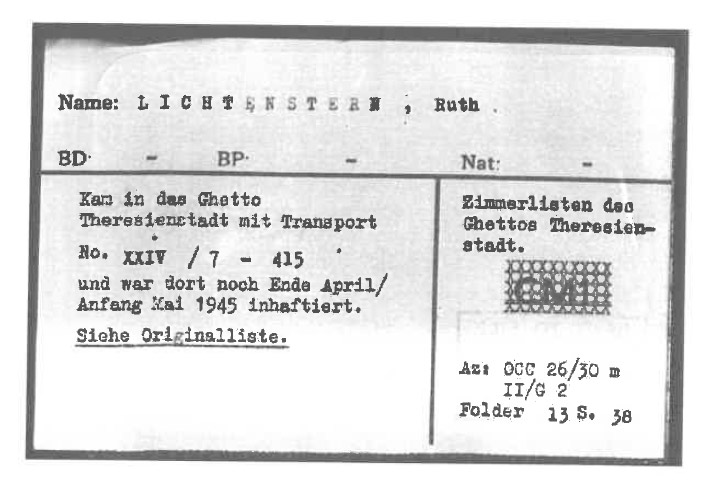

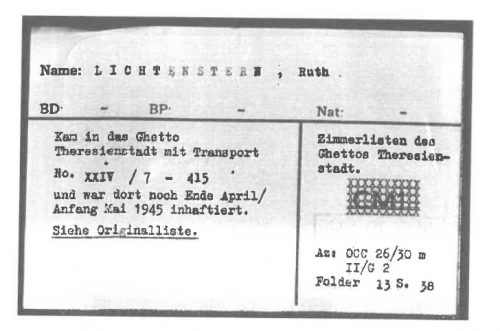

Document No 5058548#1

ITS Arolsen Archives

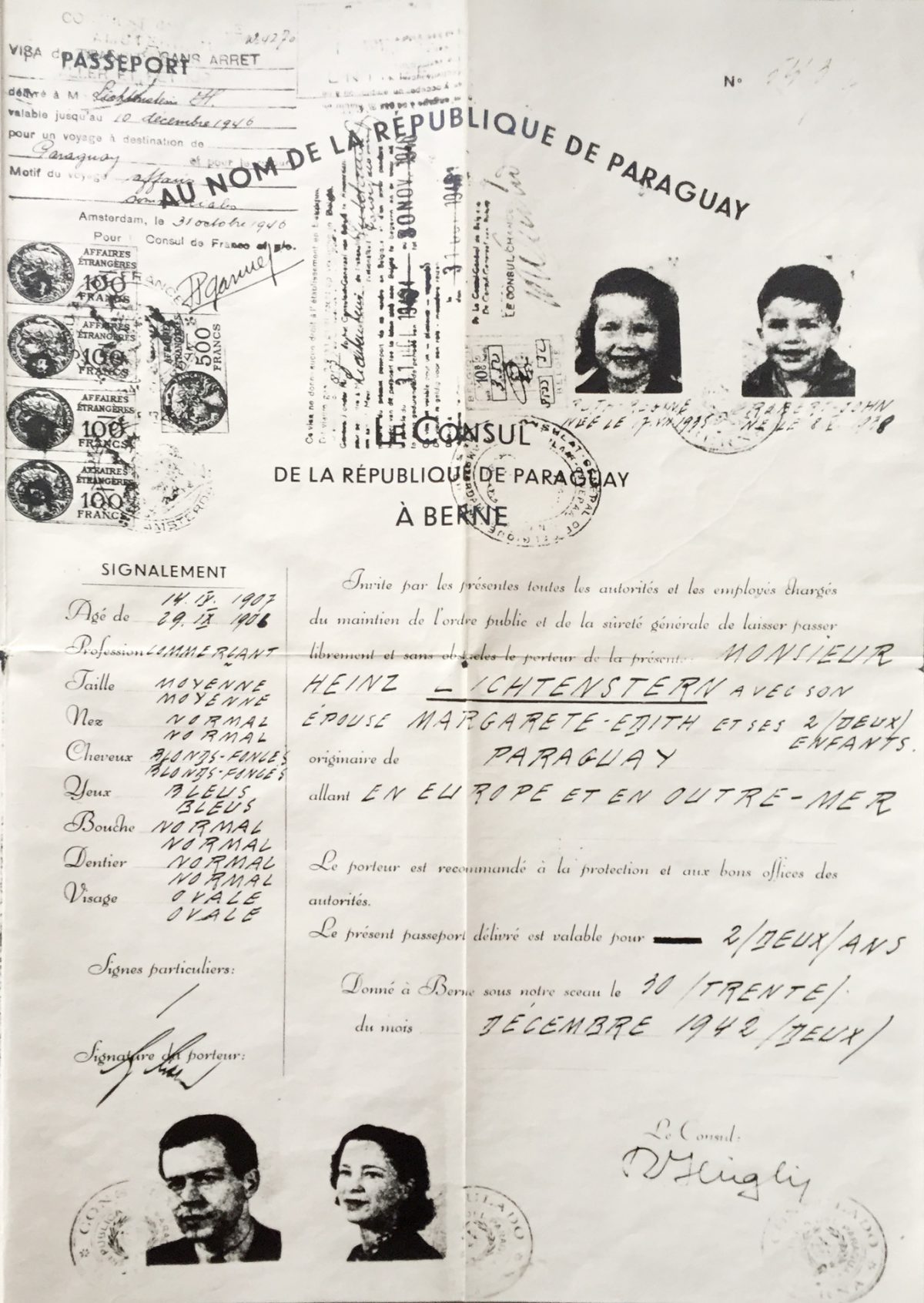

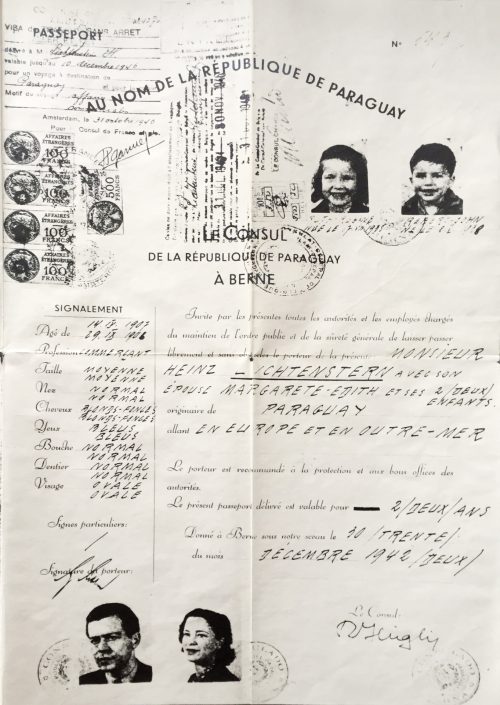

The Lichtenstern family's passport of Paraguay

Heinz Lichtenstern

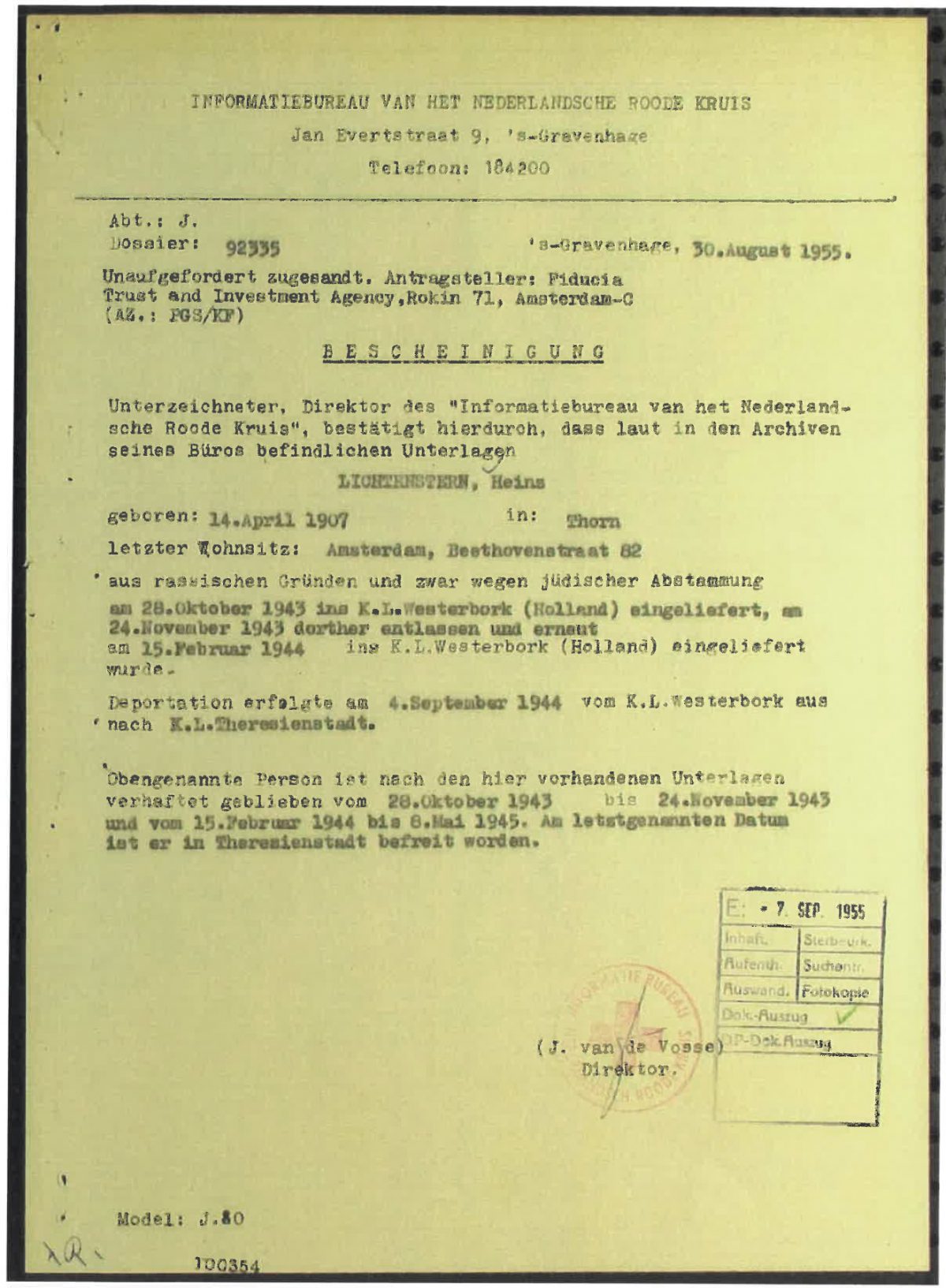

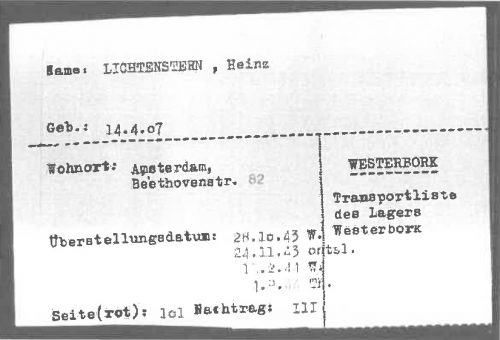

Document No 100189017#1

ITS Arolsen Archives

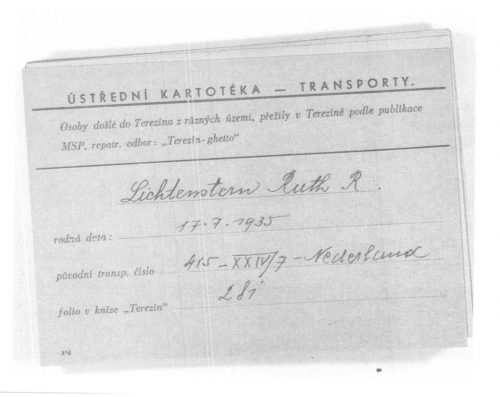

Document No 65523623#1

ITS Arolsen Archives

Document No 65523603#1

ITS Arolsen Archives

Growing up, whenever I asked my mother, Ruth “Tutti” Lichtenstern Fishman, how she and her family survived the Holocaust, her answer was always the same: “We had a forged Paraguayan passport.” I never questioned her matter-of-fact statement until I began to research and write her story, which turned into a book called Tutti’s Promise. Then suddenly, questions poured out of me, and they haven’t stopped. Questions like, who forged your passport? How and when did your father obtain it? Did he pay for the passport? If so, how much did it cost? How many intermediaries did it take for this passport to reach him?

In 1936, hoping to escape the anti-Semitism of Hitler and the Nazis, my grandfather, Heinz Lichtenstern, moved his family from Cologne, Germany, to Amsterdam in the Netherlands. However, in May 1940, the Netherlands was invaded and then life for the Jews changed forever. As a metals commodities trader, my grandfather had friends all over the world. I am certain he called on anyone he thought might be of help. At some point after the invasion, he gave all of his available cash to a friend, Egbert de Jong, who was the Rijksminister for Non-Ferrous Metals for the Netherlands. He asked de Jong to hold his money for him until the war was over. Before leaving Cologne, Heinz had been stripped of his citizenship by the Germans, who had also implemented a steep emigration tax, so he was rightfully concerned that the Germans would seize the bank accounts of Jews in the Netherlands. He also instructed de Jong to use the money, if he could, to help his family survive. I believe, he collected money from other Jews in his firm to give to Egbert de Jong to help them, as well.

In 1943, the family was transported to Westerbork, the transit camp in the Netherlands. The family included my grandparents, Heinz and Margret Lichtenstern; my then 8-year-old mother; and her 5-year-old brother, Robbie. All four of my mother’s grandparents had already been taken to the camp four months prior. After one month in the punishment barracks of Westerbork, my mother and her immediate family (that is, her parents and brother) were released back to Amsterdam. This seemed to me to be a strange occurrence, but after quite a bit of research, I discovered that my grandfather had been instrumental in turning the transit camp into a work camp: a scrap metal sorting facility. The hundreds of Jewish prisoners being put to work sorting the scrap were able to stay longer in the Netherlands, avoiding transport to points East, a fate widely known to mean death.

In my research, I discovered that Heinz Lichtenstern was named on many documents that were sent between the offices of Adolf Eichmann and Albert Speer. Speer, in charge of munitions and armaments, needed metal. Eichmann was moving as many Jews as possible to the death camps. These men were arguing about what to do with my grandfather. In February 1944, the family was re-arrested under the orders of Eichmann’s office and again sent to Westerbork. This time they were housed in the “privileged barracks.” Upon arrival, they were very happy to find that my mother’s grandparents were still in the camp; however, ten days later, all four of them were sent to Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia.

Meanwhile, de Jong used the money my grandfather had given him to obtain papers, and at some point in 1943 or 1944, my grandfather became the holder of a copy of a falsified Paraguayan passport. This life-saving document included the names of my grandfather, grandmother, mother, and uncle. The passport, numbered 543/43, was listed as having been issued on 30 December 1942. That date was probably as false as the passport itself. It was issued out of Bern, Switzerland. My mother told me that there were about 20 to 30 passports that were obtained from the same source and mailed to Amsterdam, but most were seized by censors. This was the only one of the lot that reached its intended recipient. My mother had thought that this group of passports was intended for her family alone and that there were multiple copies of the same document being sent in hopes that one would make it through. However, I believe that there were 20 to 30 different families that were intended to get these passports but that very few were received. My grandparents’ friends Moses and Gertrud Hanemann received one (#530/43), as did Caelilie Calvary (#493/43), who was a relative of the owner of the trading firm my grandfather worked for.

Along with the passport that was issued to the Lichtenstern family, there was a letter of notarization, dated 16 November 1943, which was signed by Ignaz Herzfeld, an attorney from Basel, Switzerland. I presume that the passport was brought from Bern to Basel by someone associated with the Ładoś group. How it was then delivered to Egbert de Jong and Heinz Lichtenstern, I do not know.

The Lichtenstern family remained in Westerbork until 4 September 1944, when they were transported by boxcar to Theresienstadt. Life in Theresienstadt, also known as Terezín, was much more difficult than it had been in Westerbork. All in all, conditions were harsher, there wasn’t enough food, and disease was rampant. At the end of September 1944, the Germans began to liquidate Theresienstadt. During the course of one month, there were eleven transports to Auschwitz. Approximately 18,400 men, women, and children were transported. Of those, at least 16,365 were murdered.

The first of those transports was number Ek. There was a general notice put out by the Jewish Self-Administration of the camp that announced that the transport would take 2,500 men between the ages of 16 and 55 to the German Reich to build a work camp. In reality, that train was destined for Auschwitz. As my mother tells the story, her 37-year-old father was assigned to the next day’s transport. He came to the barracks that she was housed in with her brother and mother to say goodbye. She says she had never seen him cry before and that he lay down on her bunk and hugged her and cried uncontrollably. He knew he was being sent to his death. He also knew that this meant that he would no longer be able to do anything to protect his family. He understood that they would be on one of the next transports. I can only imagine what it had been like for my nine-year-old mother to have her father crying like that while holding her for dear life.

The next morning, he reported to the transport area along with a mass of other men, who were all facing the same fate. Someone, a friend perhaps, knew of my grandfather’s Paraguayan passport. Whoever that was—another Jew who feared for his own life—he encouraged my grandfather to show his falsified document to the SS. My grandfather must have been doubtful that it would help; after all, it hadn’t kept him from being sent to Theresienstadt. It must have taken a lot of courage to step aside and present his passport, for to step out of line meant a potential beating or being shot on the spot. That moment was a defining one. The German looked at the falsified Paraguayan passport that was issued out of Bern and removed Heinz Lichtenstern from transport Ek. My grandfather was given a thin pink piece of onion-skin paper that read ausgeschieden, followed by his name, camp number, and birthday. Ausgescheiden means “withdrawn.” According to data on the Yad Vashem website, transport Ek arrived at Auschwitz, holding not 2,500, but 2,498 prisoners. Of those men, 2,016 were gassed upon arrival. I do not know how many of the remaining 482 men ultimately survived.

Most likely, without the passport, my grandfather would have been murdered in Auschwitz. The rest of his family would have, in all probability, met the same fate. But they were lucky, as most of them were able to stay in Theresienstadt together until the end of the war. Tragically, my mother’s maternal grandparents were on the final transport to Auschwitz and were gassed.

After the war, the family’s paperwork, issued by the Allied Expeditionary Forces (AEF), had them identified as “stateless,” which meant that returning to their home in Amsterdam right away—or ever—was in doubt. This is where the story of the Paraguayan passport continues. Immediately after the war it had been very difficult for stateless Jews to return to the Netherlands. The Dutch felt that they had suffered enough at the hands of the Germans. They did not want Jewish refugees, especially stateless ones who would remain in their country and, they believed, become a burden on their society. But because my grandfather possessed the false passport, someone crossed out the word “stateless” and replaced it with the word “Paraguay,” allowing my mother’s family to return to Amsterdam less than two months after liberation. The Netherlands was seemingly more willing to let a Paraguayan family than European Jews into Amsterdam, as they assumed those people would eventually want to return to South America.

The passport provided for the family a third time when, once back in Amsterdam, my grandfather resumed work to take care of his family. He continued to do what he knew best: international trading. This meant international travel, requiring a passport. But because he couldn’t just sit and wait for several months for a Dutch passport to be issued—after all, he was supporting a wife and two children, as well as his parents, who had survived the camps—he traveled throughout Europe for at least two years using that same life-saving Paraguayan passport. Every spare inch on that document is filled with entry and exit stamps.

I often think about the passport and the three ways it saved and helped my mother’s family: keeping them out of death camps, shortening their detention in displaced persons camps, and allowing my grandfather to make a living. While some of my questions regarding the passport remain unanswered, one thing is clear: Aleksander Ładoś and all of his associates in that courageous passport plan are heroes.

-K. Heidi Fishman, M.A., Ed.D.

K. Heidi Fishman, author of Tutti’s Promise, is a retired psychologist, Holocaust educator, wife, and mother of four. She lives in Vermont (USA). Her mother’s family survived the Holocaust thanks to a Paraguayan passport.