An Intermediary

Natan Eck

Nathan Eck.

Courtesy of the Ghetto Fighters' House Archives, Israel

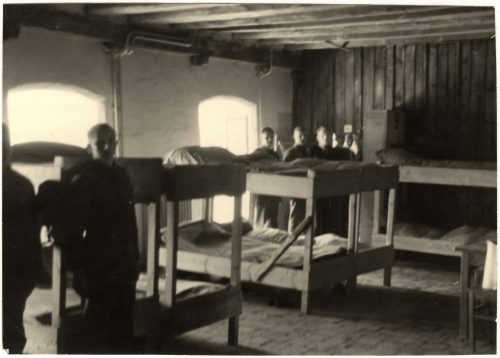

Tittmoning Internment Camp

International Committee of the Red Cross ICRC, 12/10/1942, War 1939-1945. Tittmoning. Ilag, prisoners of war camp. Dormitory, V-P-HIST-01628-13

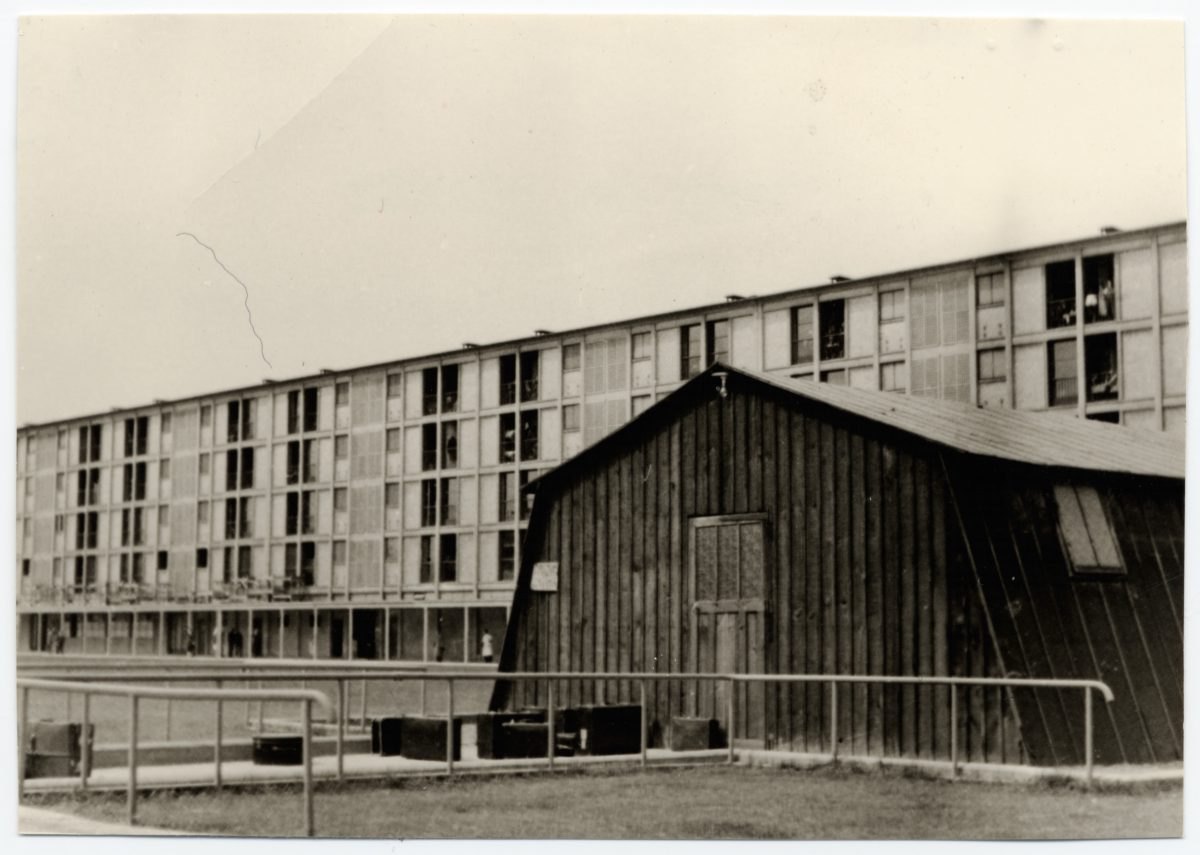

View of the Vittel internment camp. Circa 1943

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Anne Wolfe

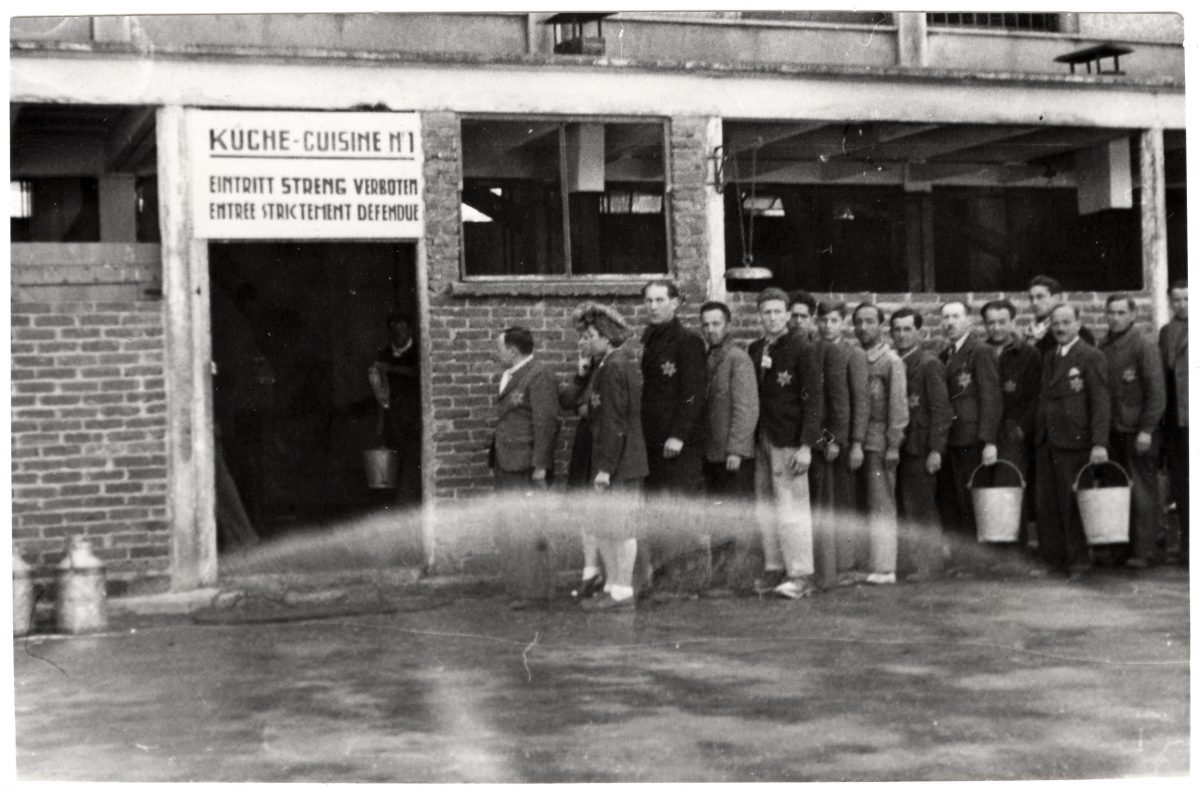

Camp for Jewish civilian internees. Waiting in front of the kitchen at mealtime.

copyright International Committee of the Red Cross ICRC, 10/05/1944, World War II. Drancy. Camp for Jewish civilian internees, V-P-HIST-00729-03A

Drancy. Camp for Jewish civilian internees. Shelter used for examination of new arrivals.

copyright International Committee of the Red Cross ICRC, 10/05/1944, World War II. Drancy. Camp for Jewish civilian internees, V-P-HIST-00729-20A

“Hello, doctor Eck,” said Abraham Carmi to an elderly man whom he met on the stairs of the Yad Vashem Institute. Carmi survived the Warsaw Ghetto, the camps of Majdanek and Birkenau and the death march. After the war he emigrated to Israel. In 1954, he found the name of Natan Eck as co-author of one of Yad Vashem’s publications. Carmi remembered him from the ghetto, from a “Tarbut” secondary school of which Eck was the headmaster and the teacher of Hebrew. He saw him for the last time on 30 June 1942, at the end of the school year. Three weeks later, the Germans commenced Grossaktion Warschau – the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto. About 250,000 Jews were then deported to the death camp of Treblinka, where they perished.

Following his discovery, Carmi went to Yad Vashem to meet his former teacher. After a moment’s confusion, Natan Eck recognized his former student. They shook hands and engaged in an earnest conversation. Until then Eck had not expected that anyone from his school survived the Shoah. Eck’s story of survival was completely different than that of his student. What figured prominently in it was a Paraguayan passport.

At the beginning of the occupation, Natan Eck fled from Łódź, where he was wanted by the Gestapo, to Warsaw, where he continued his prewar activities in leftist Zionist organizations. Following the establishment of the ghetto, he became one of the co-creators of the underground press and clandestine teaching – he published in “Słowo Młodych” and served as a headmaster in the aforementioned “Tarbut” secondary school.

Early on in 1942, Gutta Eisenzweig told Eck about a family who had obtained Paraguayan passports with the help of members of the Agudat Yisrael party who had been staying in Bern. It was probably then that he heard for the first time about the documents that gave Jews a chance for survival.

After the Germans began the liquidation of the ghetto on 22 July 1942, Natan Eck, his wife Klara and daughter Raja managed to avoid deportation to Treblinka. They reached Częstochowa, crossed the border between the General Government and the Third Reich and in the autumn found themselves in Będzin. Since the wave of deportations had already swept the ghettos in the Dąbrowa Basin, Eck believed that they would be safer there. He also hoped that it would be easier to get to neutral Switzerland from the territories annexed into the Reich, and he had contacts with Jewish relief organizations operating there which he had established back in Warsaw.

The Ecks took residence with Dawid Liwer, a local Zionist activists and member of the Jewish underground. They did not have any documents confirming their residence in the Będzin ghetto, for which they could be punished with deportation to Auschwitz. Eck wasted no time in making efforts to obtain a passport that would allow his family to leave occupied Poland. He decided to reach out to his Swiss contacts and sent a letter to Natan Szwalb from Bern who knew how to obtain the documents of Latin American countries.

Finally, in March 1943, the Eck family received a Paraguayan passport from Abraham Silberschein. Natan became involved in the activities of the committee that distributed passports obtained from Silberschein and Szwalb. He gave one of the passports to Arie Liwer, one of the most prominent members of the Jewish underground, who was also a brother of Dawid Liwer who sheltered the Ecks.

At first the Będzin activists were skeptical about the possibility of saving anyone through passports. Everything changed when Natan Eck was arrested. He showed his passport to the Germans and on the very same day he and his family were sent in an ordinary civilian train to an internment camp in Tittmoning in Bavaria.

Eck’s letters from Tittmoning, in which he described an unimpeded journey across Germany and bearable conditions at the camp, caused a sensation in Będzin. More and more people applied for the passports. A few weeks after his arrest, Eck met Arie Liwer, who had recently arrived at the camp from Będzin.

Later Natan, his wife Klara and their daughter Raja were transported from Bavaria to another internment camp for “foreigners” – to Vittel in the east of occupied France. This rather dilapidated spa town seemed a paradise to the ghetto survivors – there were clean sheets, running water and classes for children, and everyone was allowed to stroll along leafy streets and in parks.

The situation changed towards the end of 1943, when the Germans set up a commission for the verification of passports held by Jewish internees from Vittel. The documents had to be recognized by the Paraguayan authorities. Due to the war, distance and communication difficulties between Europe and South America, the exchange of dispatches took a lot of time. As early as in February 1944 the Jews from Warsaw were moved outside the camp. After a few months of waiting for an answer from across the Atlantic, the Germans decided that their hands were no longer tied concerning the Jews from Vittel as their passports were no longer viewed as a diplomatic “protective shield.”

The first transport was soon sent to the transit camp in Drancy near Paris, while its final destination was the camp of Auschwitz. Natan Eck was on the second transport from May 1944. He jumped out of the train before it reached Drancy and remained in hiding in Paris and its environs until the Allies liberated France in August 1944. The teenage Raja Eck was smuggled out of Vittel before the camp was liquidated and thus managed to survive the war; Klara Eck, however, did not manage to escape from the transport to Drancy and perished in Auschwitz.

Following liberation, Eck became engaged in Holocaust studies and disseminating memory about its victims. While still in Paris, he published poems about the Jewish martyrdom written by his friend Icchak Kacenelson, who was murdered in Auschwitz. In independent Israel he co-created the Yad Vashem Institute. Eck passed away in Tel Aviv in 1982.

From among the Jews interned at Vittel in 1943 and 1944 only a handful survived, including Natan Eck. The decision of the Paraguayan government to recognize the passports, issued after sustained pressure from the Polish Government-in-Exile, the Holy See and the Allies, reached Germany on the day in which the Jews from Vittel were dying in the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

Natan Eck survived by a miraculous coincidence. Thanks to the Ładoś passports – in the distribution of which Eck was involved during his stay in the Dąbrowa Basin – 22 Jews, including Arie Liwer, survived the war in various internment camps.

During their meeting at the Yad Vashem Institute in 1954 Abraham Carmi and Natan Eck had a long conversation about their work and current affairs. They did not talk about the war.